Tracing Remnants of the Rhode Island Slave Trade

This project has an investigative nature, and, related to it, a commentary on the power of family or kinship connections. It investigates how in the 1700’s, Rhode Island, the smallest by landmass colony of the original thirteen colonies, became the state with the highest number of voyages to the Gold Coast of Africa with the sole intent to kidnap Africans for forced labor on plantations in the Caribbean, Brazil and the British NA colonies. The Rhode Island built ships carried potent rum & other objects as part of the kidnapping ‘exchange’.

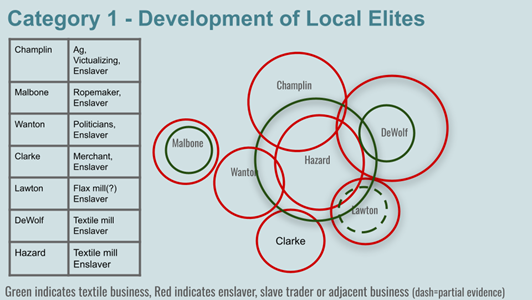

Between 1709 and 1807, Rhode Island merchants sponsored at least 934 slaving voyages to the coast of Africa and carried an estimated 106,544 slaves to the New World. From 1732-64, Rhode Islanders sent annually 18 ships, bearing 1,800 hogsheads of rum, to Africa to trade for slaves, earning £40,000 annually. Newport, the colony's leading slave port, took an estimated 59,070 slaves to America before the Revolution. Bristol and Providence also prospered from it. In the years after the Revolution, Rhode Island merchants controlled between 60 and 90 percent of the American trade in African slaves.

My preference in studying an environment as complicated as this is to separate the distinct pieces into familiar components. This pushes me in directions that would not ordinarily be linked until one base component albeit in different forms suddenly blossoms into lively streams of study and connectivity. Such is the way of textiles in a project that investigates a small group of merchants, sea captains, textile manufacturers and landowners in the 1700’s in Newport and Bristol, Rhode Island. Much of this work takes shape in the historical societies and libraries of Rhode Island and in places where slave cloth was produced and sails were sewn, hemp yarn was transformed into rigging or netting. In the context of visual language, I use a layering practice of weaving a jib sail and sewing scaled down versions including the roping, clews, etc. The places of textile manufacturing and markets are woven by team members and contain notes of where a plantation owner might purchase slave cloth and humans. The familial connections of the early Rhode Island merchants extended to business ties in the rum producing industry, the insurance of the slave ships and the provisioning of the schooners, sloops and brigs that sailed the Transatlantic Route to the Cape Coast of Africa.

Loosely categorized, this work studies each category individually while identifying the common threads between the three categories. Although ordered for organizational purposes, there is no particular ‘order’’ as each informs the other providing additional information of validation or further questions.

First, I examine the generational trajectory of the Hazard family and those who founded Newport, I study who they marry and what they do. Intermarriage and interbusiness relationships are prevalent leading me to apply the kinship theory - state of being related for both family and business reasons.

Here the focus is on the slave trade and the function of textiles used to kidnap, transport and sell Africans to offset the cost of labor on plantations in the West Indies and the Southern colonies of British North America. Cordage, sails and suicide netting were chief among the critical textiles on the slave ships. I’ve begun weaving a sail representative of the linen sails woven in the 1700’s for the merchants of Rhode Island as they traded rum for Africans. This sail is being woven at The Weaver’s Croft in Marshfield, Vermont according to the specifications of the British Royal Navy guidelines of 1796.

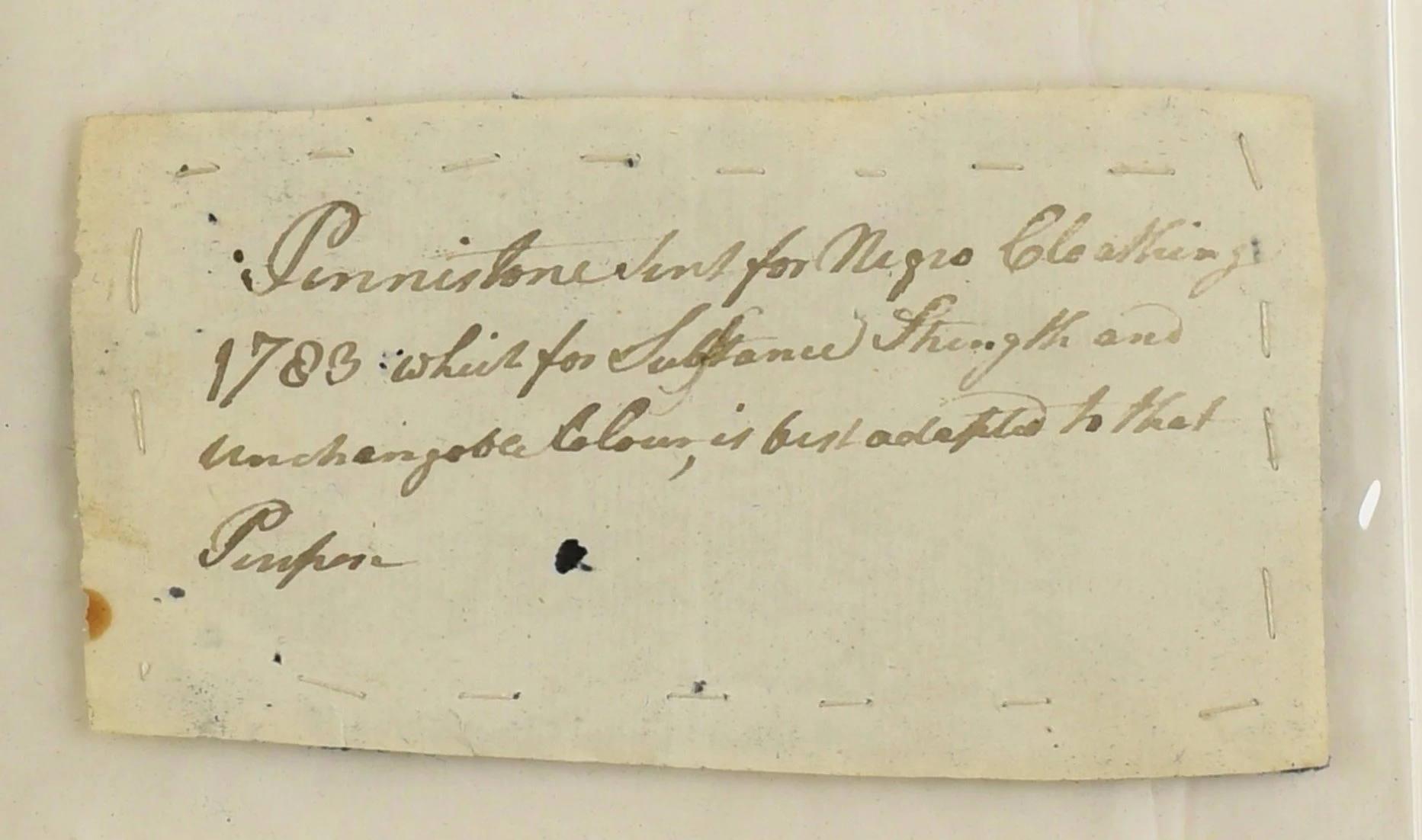

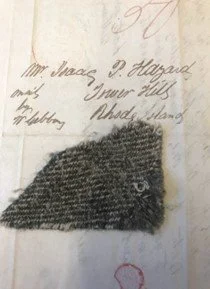

The third centers on the plantation economy, the supply of textile materials to the plantation owners in the Southern British American colonies and the West Indies. Rhode Island textile manufacturers such as the Hazard family in Peace Dale, RI were instrumental in the supply of ‘Negro Cloth’ for field hands in the cotton fields as well as the beet fields in the West Indies. (See section ‘Textiles on the Slave Economy’)

Sail Plans of Sloops in the 1700s typically used in the Transatlantic Voyages. Prints by author.

Letter from Thomas Hazard of Peace Dale, Rhode Island as he is selling Negro Cloth to the Louisiana plantations

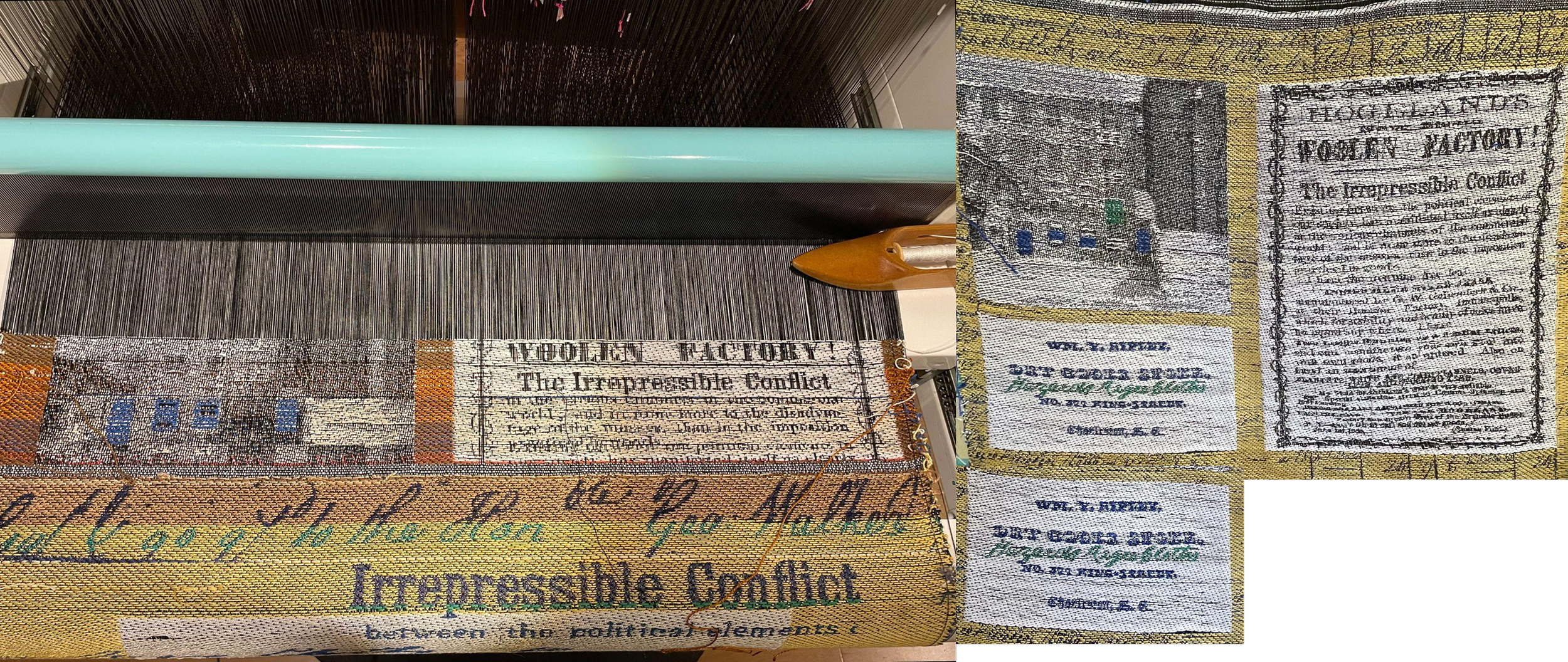

Woven Illustrations of the Slave Trade

Archival Material Woven by Robin Mulle- these were advertisements of Negro Cloth from the Peace Dale Manufacturing Plant for plantation owners in the South.

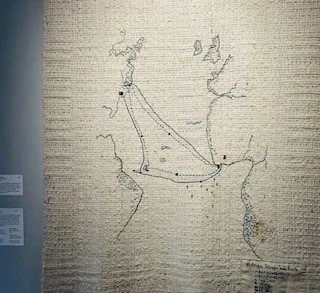

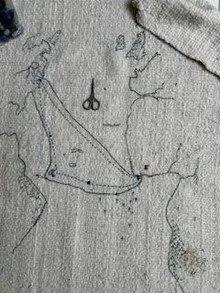

Detail of Woven Map of Transatlantic Slave Voyage from Newport, RI to the Cape Coast, Africa

Detail of Woven Map of Transatlantic Slave Voyage from Newport, RI to the Cape Coast, Africa